We choose to do these things because they are hard

Posted: November 21, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentIn 1962 John F Kennedy made what is probably the iconic speech on space travel,

One of the key points in the speech was answering “why go to the Moon?”,

“But why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas? We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too”

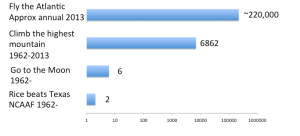

Today I was thinking about this speech and I thought, how many times have these hard things been done since then. Well here’s the answer,

Sources, flights (I couldn’t find long-term historical traffic data), Everest (-9 ascents pre1962), Rice vs Texas. For the non-Americans the last example was because the speech was made at Rice University and every few years Rice plays the University of Texas, a school 16 times its size, at American football.

And if you think it’s bad for Rice try being a Hawaii Rainbow Warriors (7-28 last 3 seasons) fan like me.

Henderson, the first distance to a star and Scottish confidence

Posted: November 14, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: history of astronomy 1 CommentOne hundred and seventy five years ago a Scottish astronomer published the result that he would become famous for. Unfortunately it was the timing of the result that was the most note-worthy thing.

Thomas Henderson didn’t follow what we would now consider a typical astronomical career. He started out in Dundee as an apprentice to a lawyer. Six years later he moved to Edinburgh to further his law studies eventually becoming secretary to the Lord Advocate (similar to the Attorney General in other countries). All the while Henderson had been developing his astronomical hobby, focussing on computational methods. It was his brilliance in this that resulted in him determining more accurate methods to work out the timing of the Moon’s passage infront of stars. This calcualtion brought him to the attention of Thomas Young who at the time was running the Naval Almanac Office, in-charge of accurately calculating the timing of astronomical events. He applied for a job at the Almanac Office after a posthumous reccomendation by Young but was turned down. He was also turned down for a job at Edinburgh University around this time. Henderson then took a job working at the Cape Observatory (yes, he had to move halfway round the world to stay in astronomy, how modern). He spent a year there, working ridiculous hours making a massive number of astronomical observations. This appears to have burnt him out and he moved back to Edinburgh to become the first Astronomer Royal for Scotland. But he brought back with him the dataset that would see his name go down in history.

The distance to stars can be pretty hard to measure. While the noted astronomers of antiquity had noted “the fixed stars” as opposed to the wandering planets, by Henderson’s time it was understood that stars moved slowly across the sky. This indicated that the stars weren’t infinitely far away and (due to its high motion) that Alpha Centauri was probably quite close. The best way to estimate the distance to a star is using trigonometric parallax, taking advantage of the subtle changes in the point of view a star is observed from at different stages in the Earth’s orbit.

This first step on the stellar distance ladder became one of the big science goals of the mid-19th century. Henderson was one of the best in the world in astronomical calculations and soon after returning from the Cape, he had noticed an oscillation in the position of Alpha Centauri. This was about an arcsecond, roughly the size of a Coke can viewed 440km away. This made Alpha Centauri about 3.25 light years away (compared to the true distance of 4.4 light years). However Henderson wasn’t sure, he thought his instrument may be suspect so he waited for more observations from the Cape to confirm his results. Unfortunately his lack of confidence bit him, he was beaten to the first parallax measurement by the Prussian astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel nipped in and measured the parallax of another fast-moving star 61 Cygni in 1838, two months before Henderson’s publication.

Henderson’s lack of confidence may have stemmed from previous parallax measurements which were later shown to be nonsense. However it may have stemmed from the inherent lack of confidence Scots have. Scottish people are among the least confident in the developed world, Scottish satire writers pick “Lloyd, I’m ready to be heartbroken” to sum up the Scottish national football team. Perhaps the best summation of this is Gordon McIntyre’s, “I hate the way we expect to fail, and then we fail, and then we get bitter because we fail.” A nation defined by glorious failure, shy about its history of discovery, doesn’t produce risk takers.All that said, if I’d have been in Henderson’s position, I would have done the same. We’ve all seen massive “discioveries” knocked down by data released soon after and in science it should be more important to be right than to be first at all costs.